About Indonesia

- Population: 280 mn

- Total area: 190.5 mn. ha

- Agricultural land: 55 mn. ha

- Arable land: 24 mn. ha

- Irrigated land: 7 mn. ha

- Forestry land: 129 mn. Ha

- Rice land: 14 mn. ha

- Paddy Yield: 75 MMT

The Indonesian rice industry stands as a cornerstone of the nation’s economy, not only for its substantial contribution to agricultural output but also for its role in providing livelihoods to millions of rural workers. Rice, being a staple food in Indonesia, holds cultural and socioeconomic significance, shaping dietary habits, rural livelihoods, and even political discourse.

- A country with a population of more than 250 million people, it is an interesting market for food producers, particularly due to the significantly increasing number of middle-class population that consumes more quality products.

- Indonesia’s population growth is approx 1.49%.

- The advancing population number can be viewed as an opportunity for business growth in food industry, including rice industry.

- Total rice production is projected to increase largely due to yield improvement of 1.25%, with a marginal increase in harvested area. Total rice consumption (39.55 mmt) is growing at 0.90% per year due to population growth, as per capita consumption is projected to decline marginally.

- Indonesia sources nearly 5% of its domestic rice needs from imports and has long been aiming for self-sufficiency.

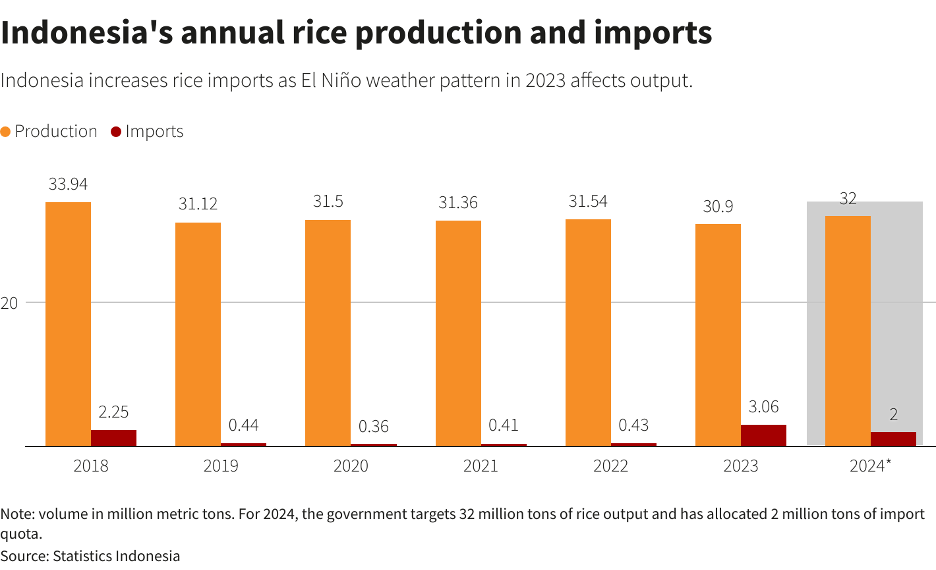

- Rice imports declined dramatically, from 3.1 mmt In 2010 to 0 in 2016, due to increased domestic production and local politics.

- In 2023-24 imports have increased dramatically due to El-Nino

Indonesia’s rice market is fragmented.

- Approximately 80% of the total rice mills comprise of small plants, and only about 5% are of large-capacity. Meanwhile, the remaining 15% are categorized as peddler mills.

- The geographic distribution of rice mills is similar to that of rice farms.

- Most rice mills in Indonesia are privately owned, although BULOG operates 132 rice mills spread throughout Indonesia.

- Milling rates are relatively low on average (about 63.5 %) but can be as high as 69 % for dry paddy rice at efficient mills.

- Mills mainly market rice through private channels (traders and wholesalers), which account for 90 percent of the rice market, selling smaller amounts to BULOG and directly to retailers.

- Approx 56 % of mills are in Java and 20 % in Sumatra.

Indonesia’s key rice growing areas

The milling sector in Indonesia is highly fragmented, with over 100,000 rice mills. The bulk of these (about 93,500) are small mills with husker-polishers and a capacity of less than 1 mt per hour. There are also approximately 5,500 “modern” mills with facilities to dry, clean, mill, polish, and sort rice: their capacity is over 2 mt per hour.

However, many of these mills are aging and inefficient. New, large mills have entered the sector in recent years, some with a capacity of 30 MT per hour. These mills operate on a business model referred to as “paddy to rice” whereby they aim to mainly source wet paddy rice directly from farmers, dry and store the paddy rice, and control the processing chain to maximize yields and quality. They can supply all markets but are targeting higher-quality segments, mainly premium branded and packaged rice distributed through modern outlets in urban areas. According to one Indonesian rice miller, a polarization is occurring in the Indonesian milling sector, as small mills continue to enter the market along with the large mills, while medium-sized mills exit. This phenomenon was attributed to the lack of entry barriers for small mills, high overhead for medium-sized mills, and the role of BULOG purchases in local markets.

The competitiveness of Indonesia’s rice sector has been enhanced by the use of high-yield variety seeds, fertilizers and pesticides, and irrigation, which have contributed to a long-term growth in yields. New private investment in large, modern mills is also improving the competitiveness of Indonesia’s rice sector. In addition, a depreciating currency makes domestic rice less expensive than imports.

Rice is grown by approx. 50 % of Indonesian households. The major rice-growing areas are Java (approx. 60 % of total production) and Sumatra (approx. 18 %).

Indonesian rice farms are relatively small—0.67 hectare (ha) on average. Irrigated rice-growing farms are smaller, on average, than dryland farms. The majority of farms (84 %) are irrigated and grow lowland rice. Most Indonesian rice farmers are organized into one of more than 100,000 regional groups, which provide members with technical and marketing assistance and help them obtain credit and inputs (such as seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides). Farmers sell their paddy rice mainly through private channels (e.g., traders, millers, wholesalers, and retailers).

Costs of Production Are Relatively High

Indonesian paddy rice production costs are high relative to those of other regional producers, particularly the major exporters (India, Thailand, and Vietnam). According to a survey, paddy rice production costs totaled approx. US$294 per mt. Land was the largest cost item; rising demand for land for non-agricultural use has increased land values, and many rice farmers have sold their land and rented it back, increasing their costs. Labor was the second most expensive item; competition for labor from non-agricultural activities has pushed up wages, and many farmers have employed hired labor, as they and their families shift to other employment. Fertilizer and other chemical input costs together accounted for 14 % of total costs; this share likely would have been higher in the absence of the government fertilizer subsidy. Despite relatively high costs, survey participants reported a positive average net income of US$631 per ha. Reportedly, milling costs are also high relative to those for other regional producers and have been rising. Mills that buy wet paddy rice generally calculate costs based on paddy rice prices and a milling rate of 55–56 percent. Millers also report profits that are generally between 100–200 rupiah (US$0.01–US$0.02) per kg.

The government played a crucial role in the rice economy, implementing policies to ensure price stability for urban consumers and achieve self-sufficiency in rice production. These measures included promoting high-yield seed varieties through government extension programs, investing in irrigation facilities, and regulating domestic rice prices through the National Logistical Supply Organization (Bulog), the government's rice trading monopoly. In the 1970s, Indonesia was a major rice importer, but by 1985, self-sufficiency was attained after six years of remarkable annual growth rates exceeding 7 %. Government investments in irrigation significantly contributed to the increased rice production in Indonesia. To balance consumer affordability and producer incentives, Bulog's operations evolved to consider both factors. Domestic rice prices were gradually increased during the 1970s, although generally kept below world prices. However, during several periods in the 1980s, domestic prices were maintained above world prices. Bulog influenced the domestic rice price by operating a buffer stock of around 2 million tons, purchasing rice when prices fell and releasing supplies when prices rose above the ceiling. The margin between the producer floor price and urban ceiling price allowed private traders to operate profitably, and Bulog's distribution was limited to less than 15 % of total domestic rice consumption in a given year.

The Indonesian government uses two approaches on both ends of the chain to reach rice self-sufficiency. On the one end, it encourages farmers to increase their production by stimulating technological innovation and by providing subsidized fertilizers. On the other end, the government tries to curb people's rice consumption through campaigns such as "one day without rice" (per week), while promoting consumption of other staple foods.

As Indonesia's population continues to grow, thus implying more mouths that need to be fed in the future, the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) as well as several big Indonesian companies have recently initiated partnership programs with smallholder rice farmers with the aim of increasing rice production through the use of new technologies and innovative financing programs.

Indonesia Embraces New Thinking Amid Rice Crisis

As the effects of climate change become more apparent, long-held traditions will need to be resurrected. Others will need to be abandoned. Indonesia is facing agricultural challenges due to climate change impacts like delayed and erratic rainy seasons, prolonged droughts, and an increased risk of crop failures. The 2023 El Niño event caused a drought that reduced national rice production by 0.23% compared to 2022. The government plans to import 1 million tonnes of rice from India to ensure sufficient supplies.

These issues highlight the need for Indonesia's agricultural sector to adopt climate adaptation strategies to boost resilience against climate change impacts. However, climate change is still an emerging concern, often viewed narrowly as just an environmental issue by many agencies and planners.

Greater coordination across government agencies is needed to incorporate climate adaptation into agricultural and rural development programs. Tapping into traditional farmer knowledge about climate-resilient practices could also help develop appropriate adaptation strategies.

Improving access to information and technology for the country's 38.8 million farmers spread across villages could facilitate adaptation. Strategies to reduce Indonesia's significant food waste of 23-48 million tonnes per year and promote more sustainable consumption patterns could complement production-focused efforts.

Overcoming long-standing cultural traditions around food preparation and ceremonial food practices that contribute to waste will require a nationwide shift in attitudes and habits. Addressing both production and consumption issues is key for ensuring Indonesia's food security amid climate change.

Other Challenges

Regeneration of future farmers. Indonesian rice farmers are ageing. The involvement of young generation in the agricultural sector is declining due to limited farmland and because it is perceived to have little (financial) reward.

Gender gap. Women make essential contributions to rice farming. However, they have limited decision-making capacity within the household or the farmers' organisation. Most of the cultivation process, from planting to harvesting, is done by women, while men take the decisions for selecting what rice varieties to plant and harvest.

Typically, planting for Indonesia's main rice crop begins with the start of the wet season in October, with harvesting in February-April. The country produces two rice crops, with the harvest during the October-April wet season accounting for 55% of annual output.

Signs of the expected 2024 decline are apparent with the farm ministry reporting the area planted with rice in the fourth quarter of 2023 dropped to 2.91 million hectares (7.2 million acres), below the target of 3.53 million hectares (8.7 million acres). Lower output would mean higher imports and Indonesia has already approved 2 million tons in 2024, a quarter of which is expected to arrive by March, officials said. In 2023, it imported 3.06 million tons of rice, a near-record.

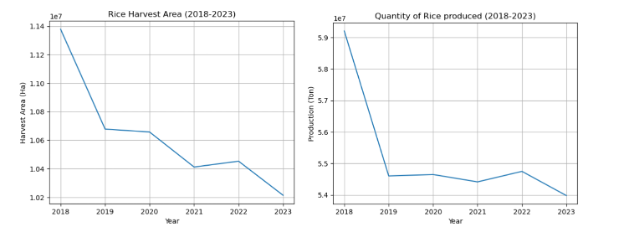

Decrease in rice production from 2018 to 2023 suggests stagnation in productivity growth within rice farming. This stagnation is further corroborated by the gradual reduction in the harvested area, indicating a limited expansion of agricultural practices.

A government handout scheme launched last year providing 10 kg of rice monthly to 22 million lower-income households, has helped eased some of the pressure, although lower-middle class households are not covered.

Purchase Patterns: A Glimpse into Consumer Behavior

Middle-aged consumers (45-54) exhibit a preference for procuring rice from fresh markets and wholesalers.

Notably, 67% of respondents in this age group spend more than 12,000 IDR (EUR 0.73) in a single transaction and buy at least 5 kg. Intriguingly, the majority (61%) of those aged 25-34, spending 14,001 IDR (EUR 0.86) and above on rice, signal a shifting trend in purchasing behavior. Quality and price emerge as the top considerations when purchasing rice. While 61% of those aged 35-44 prioritize price, nutritional value is crucial for 39% of the 18-25 age group. The top five factors influencing choices include quality (70%), price (59%), nutritional value (34%), food safety (30%), and the type of rice (28%).

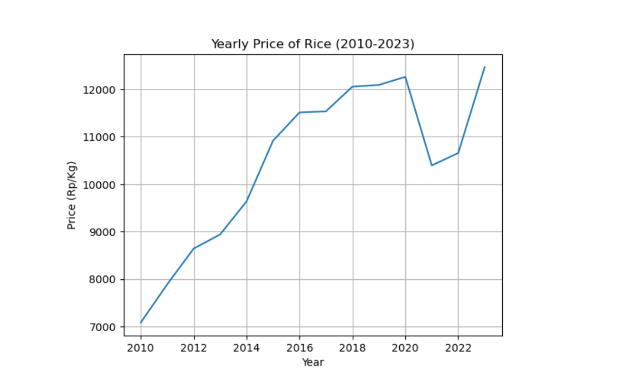

From a modest level of slightly above 7,000 rupiah per kilogram in 2010, the price of rice surged to nearly 13,000 rupiah per kilogram in 2023, with occasional dips like the notable decrease to 10,500 rupiah per kilogram in 2021. This overall upward trajectory underscores the indispensable nature of rice within Indonesian society. As a staple food, rice carries not only economic weight but also deep cultural and social significance, with its price fluctuations directly influencing the daily lives of millions of Indonesians, shaping their dietary habits, household budgets, and even cultural traditions. The surge in rice prices reflects a complex interplay of market forces, environmental factors, government policies, global market trends, and, most importantly, the enduring demand for rice among Indonesians themselves. The fluctuations in rice prices highlight the intricate relationship between this essential commodity and Indonesia's economic and social fabric.

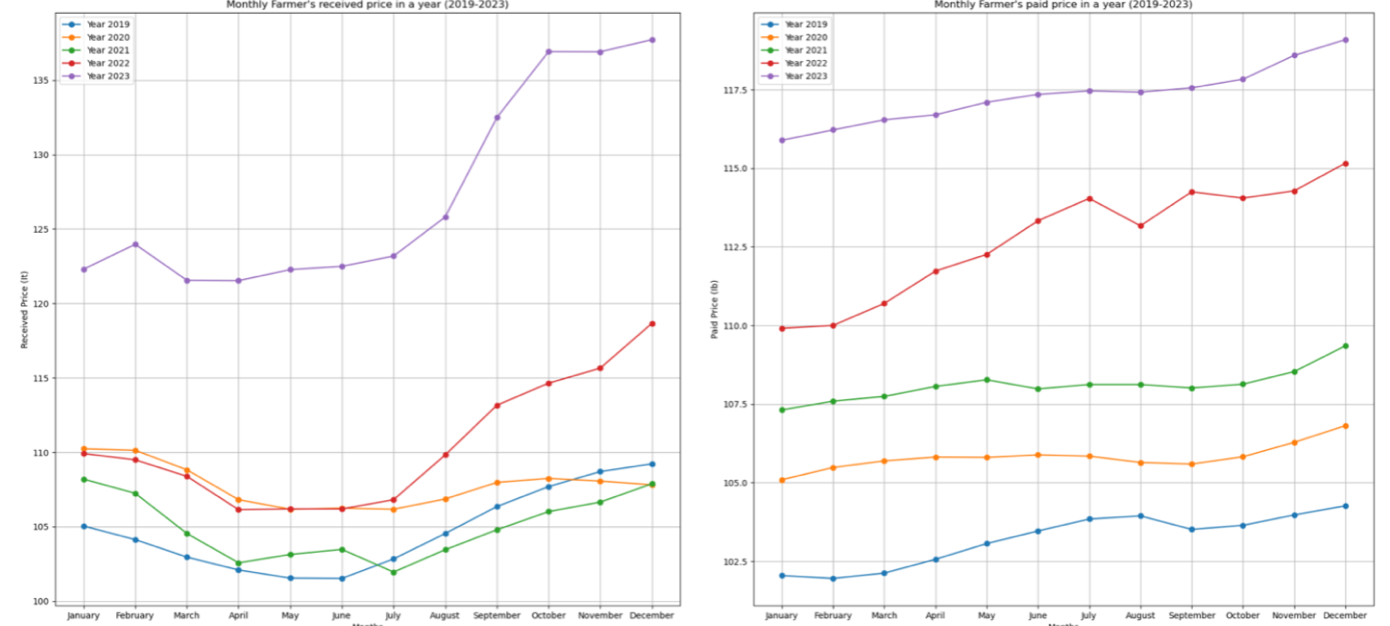

The rising costs of inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and labor have outpaced the increases in output prices, leading to a net reduction in income for rice farmers. This imbalance has eroded the profitability of rice farming activities as the gap between revenue and expenses continues to widen gradually. Consequently, farmers are facing mounting financial pressures, exacerbated by stagnant productivity levels and a shrinking harvested area. Despite the higher prices fetched for their produce, the disproportionate escalation of input costs has undercut the potential gains, leaving rice farmers in an increasingly precarious economic situation.

This imbalance also hinders investments in technological innovation and efficiency improvements.

Indonesia's labor-intensive rice farming industry is facing challenges due to rising wage costs driven by productivity gains in other sectors like manufacturing. While wages are increasing in rice farming, productivity levels have not kept pace. This mismatch between higher labor costs and stagnant productivity has led to an increase in rice prices, impacting both consumers who rely on affordable rice as a staple food, as well as producers struggling to earn fair returns. The Indonesian government finds itself in a delicate position, needing to strike a balance between keeping rice prices affordable for its population while also ensuring that rice farmers receive adequate compensation for their crops to maintain profitability and sustain production levels. Navigating this tension between consumer interests and farmer incomes poses an intricate policy challenge.